In the wide, muddy sweep of the Missouri River, where the current pulls like an old grudge and the bottom hides secrets in every snag, Jesse Lance found himself locked in a battle that any fisherman worth his salt dreams about. It was October 25, a crisp fall day near Kansas City, and what started as a routine outing in his 17-foot Alumacraft turned into a showdown with a blue catfish so enormous it could've eyed a feral hog for lunch. Lance, a guy who knows the river's moods like the back of his callused hands, hooked into something that tipped the scales at well over 130 pounds—big enough to eclipse the state's standing record, if only he'd hauled it to a scale instead of sending it back home.

Lance wasn't out there chasing glory that morning. He'd launched his boat into the familiar churn of the Missouri, the kind of water that tests a man's patience and gear in equal measure. Armed with chunks of silver carp for bait—those invasive Asian carp that have turned into a fisherman's reluctant ally—he settled into what he calls his honey hole, a spot where the river's edge meets a subtle drop-off. For the first 30 minutes, though, it was dead quiet. No tugs, no runs, just the slap of water against the hull and the distant hum of traffic from the city. Frustrated but not defeated, Lance did what any smart angler does: he picked up the phone. A quick call to a buddy who'd fished these bends before pointed him upstream to fresher ground. "Why fight the river when you can let it show you the way?" Lance later reflected, chuckling at how a simple conversation shifted his luck.

The new spot was a classic catfish haunt—a stretch of sandy bottom dotted with fallen trees, their branches like skeletal fingers offering cover to whatever lurked below. Water depth? Barely four to six feet, shallow enough that you could almost see the gravel shifting underfoot if you waded in. Lance fired up his sonar, that electronic sixth sense every serious river rat swears by, and there it was: a blip on the screen so massive it looked like a submerged log had come alive. Heart pounding, he rigged up heavy. We're talking 80-pound braided line spooled tight on his reel, a 150-pound monofilament leader to handle the abrasion from those gnarled logs, and a beefy 10/0 circle hook threaded with a fresh slab of silver carp. He dropped the bait and waited, rod tip dancing lightly in the breeze.

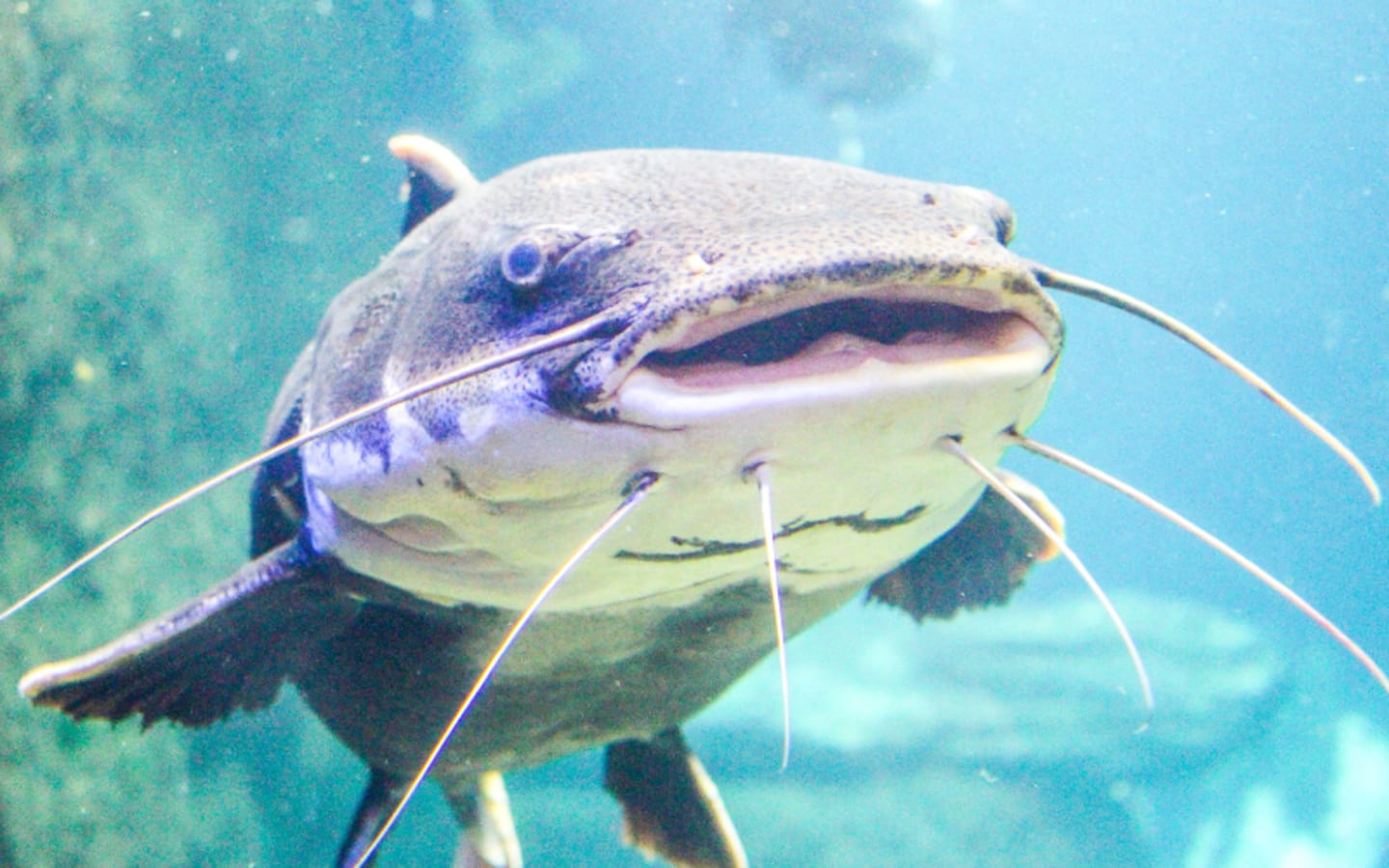

It didn't take long. The line went taut, then screamed off the reel as the fish inhaled the offering and rocketed toward the river's deeper heart. Blue catfish don't mess around—they're built like armored torpedoes, with heads broad as dinner plates and whiskers that sense a meal from a mile away. This one was no exception. Lance described the strike to Wired2Fish as feeling like tying into a freight train: instant pressure, then a bolt that peeled line off his reel faster than he could thumb the drag. For the next 10 minutes, it was pure grit. The fish surged left, then right, testing every inch of that heavy tackle. Lance backed down on the drag just enough to keep contact without snapping the line, his boat drifting with the current as he played the beast close. Sweat beaded on his forehead despite the cool air, arms burning from the steady pull. "You don't win those fights by muscling it," he'd say later. "You wear 'em down, let the river do half the work."

Finally, after what felt like an eternity compressed into those frantic minutes, the catfish broke the surface boatside. And that's when reality hit harder than the hookset. This wasn't some 50-pounder you scoop up with a quick net swipe. No, this blue was a titan—its body thick as a man's thigh, tail flaring wide enough to stir a wake. Lance, who's no lightweight himself at 230 pounds and 5-foot-9, stared down at something that dwarfed him. "It looked bigger than me," he admitted, eyes wide in the photos he snapped before the release. The fish's mouth alone was a cavern, lined with sandpaper lips and teeth that could grind bait to paste. Trying to net it? Forget it. The hoop was too small, the frame too flimsy for a load like that.

That's when Lance improvised, the way you do when the moment demands it and there's no room for second-guessing. “I had one hand on my fishing rod, the other holding the net, and I needed both hands to get the fish because it wouldn’t fit inside the net. I put on a glove, set my fishing rod down and used both hands to grab the catfish by its mouth.” Risky as hell—I've heard tales from buddies down in Florida who tried the same with snook and ended up swimming for their lost rods. But Lance pulled it off. Glove gripping the lower jaw, he heaved with everything he had, lifting just enough to swing the monster's head over the gunwale. The catfish thrashed once, a powerful roll that sent spray flying, but Lance held firm. For a heartbeat, the fish lay partly on the deck, its scales glistening like oil in the sunlight, gills flaring in protest.

He didn't waste time gawking. Out came the phone for quick videos and shots—proof of the impossible, frozen in pixels. One glance at the scale slung over the side read 126 pounds, but with the tail still dangling in the water, Lance knew it was lowballing. "Over 130, easy," he figured, picturing how it'd tip a certified scale at the marina. That number echoed in his head like a siren's call. Missouri's blue catfish record has stood for 15 years now, a 130-pound behemoth pulled from the same river by Greg Bernal of Florissant back on July 20, 2010. Bernal's fish was a legend, netted on a muggy summer day and immortalized in the state's record books. Lance's catch? It would've shattered that mark, rewriting the chapter on what the Missouri can produce.

But here's the part that sticks with you, the reason this story lingers like the smell of river mud on your boots. Lance let it go. No fanfare, no rush to the weigh station. Just a careful slide back over the side, the catfish slipping into the current with a swirl and a flick of that massive tail. Why? Because out there on the water, where the days blend into seasons and the fish become part of the place, you start thinking bigger than a plaque on the wall. "That fish is back out there, able to make bigger fish," Lance said, his voice carrying the quiet wisdom of someone who's spent enough dawns on the river to know its rhythms. Releasing it keeps the gene pool strong, the food chain humming. Blues like that are apex predators, vacuuming up shad, drum, even those pesky carp, and keeping the ecosystem from tipping out of whack. In a river scarred by floods and barge traffic, every survivor counts.

Word of the catch spread fast, of course. Lance shared the footage on Instagram through TwistedCatOutdoors, and it lit up feeds from Branson to the bootheel. Anglers chimed in with their own war stories— that 90-pounder from the Osage, the one that broke the leader on a trotline down by Hermann. But beneath the likes and shares, there's a deeper pull for guys like Lance. Fishing the Missouri isn't just about the bend in the rod or the weight in your creel; it's about those solitary hours when the world narrows to the line in the water. It's the call to a friend that turns a slow morning around, the sonar ping that promises adventure, the raw thrill of lipping a fish that could snap you in two. Lance walked away empty-handed in the trophy sense, but richer in the ways that matter—another scar on the hands, another tale for the cooler at deer camp.

As the leaves turn and the river cools toward winter, Lance is already plotting his next run. Maybe it'll be cutbait under the Highway 65 bridge, or drifting worms in the tailwaters below the dam. Whatever it is, you can bet he's scanning those sandy flats, eyes on the sonar for that telltale shadow. The Missouri gives up its monsters grudgingly, but when it does, it reminds you why you keep going back. That catfish is out there still, growing fatter on the current's bounty, waiting for the next hook—or maybe just the next story. And for the rest of us, nursing our coffee and dreaming of our own honey holes, it's a hell of a yarn to carry into the off-season.